By Edmond Y. Azadian

On August 5, a bell rang in Hiroshima exactly at the hour when 65 years ago the first atomic bomb was dropped, scorching to death 145,000 people in a brief moment. The tolling of the bell reverberated around the globe through the electronic media, reminding the world of the anniversary of a great human tragedy of historic dimensions.

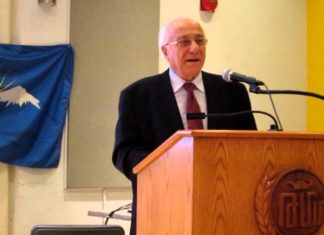

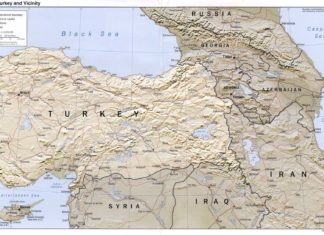

The same day, another anniversary came and passed, almost unnoticed, even by Armenians whose lives it had impacted irreversibly. Only the state TV channel in Armenia broadcast a three-minute footage remembering the 90th anniversary of a political act to restore home rule in Cilicia, now called Chukur Ova, situated on the Mediterranean Sea Coast of the present Republic of Turkey.

Indeed, August 4 and 5 were eventful days in Cilicia, raising hopes of achieving home rule by the Armenians, who were promised by the Allies, especially as a compensation for Armenian participation in World War I on their side.

What happened on August 4 and 5, 1920, has a long and sometimes intricate background.

Armenians had inhabited Cilicia many centuries before Seljuk Turks appeared in that region. An Armenian kingdom even ruled that territory between the 10th and 14th centuries, when the Memluks deposed the last king, Levon VI Lousignan, and took over the country, in 1375 AD.