By Sevag Hagopian

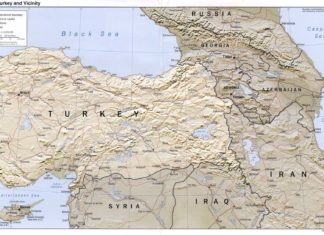

Although it is yet early to discuss the upcoming parliamentary elections of 2013 here, since it has not officially been launched, but the Armenian parties are already polarized, especially the alliance of the Tashnag party with General Michael Aoun’s Change and

Reform bloc — and consequently with Hezbollah — worries many Armenians. Furthermore, the Tashnag leaders have been unconditionally backing Aoun’s dangerous and adventurist strategy regarding regional issues and his collaboration with the Syrian regime and its Iranian counterpart. Aoun, the former Lebanese army commander and current politician and leader of the Free Patriotic Movement, declared “The Liberation War” against the Syrian Occupation on March 14, 1989. He was driven out of power by Syrian Forces on October 13, 1990 and was forced into exile in France, where he remained until 2005. While in exile, he appeared before a US Congressional subcommittee to support the Syrian Accountability

Act, which was designed to punish Syria’s regional role. He returned to Lebanon on May 7, 2005, after the assassination of Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri, 11 days after the withdrawal of Syrian troops. After his return, he controversially shifted to adopt a pro-Syrian agenda (according to many analysts, for some personal ambitions to achieve the presidency of Lebanon) going as far as signing a memorandum of understanding with pro-Iran Hezbollah in 2006. Aoun, currently a member of parliament, visited Syria in 2009. He leads the “Change and Reform” parliamentary bloc of 27 members that include the Tashnag members of parliament.

It is even more worrying the irresponsible statements of Tashnag representatives in public announcements and in private salons. The language and terminology used are surprisingly similar to those of Aoun’s and those of Hezbollah officials reading many controversial Lebanese issues, like for example, the UN Special Tribune for Hariri’s case against the Syrian regime.

I have many questions for the Tashnag leaders in Lebanon. What is the benefit of the Armenian-Lebanese community in general, and the Tashnag party in particular, in backing Aoun’s political agenda? Is this a political adventure practiced by the Tashnag party