By Daphne Abeel

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

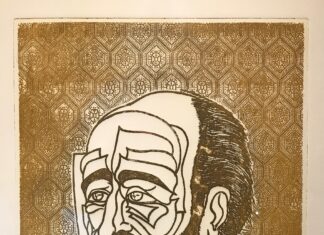

The new publication of a novel by Nobel Prize-winning author, Orhan Pamuk, is not truly a new book. Silent House, expertly translated into English by Robert Finn, was first published in Turkish in 1983. Pamuk, now in his late 50s, was likely still in his 20s when he wrote it, and it should be viewed in its context as an early or even juvenile work, which, in many respects, prefigures many of the author’s later preoccupations and obsessions.

The political and historical background of the story is the lead-up to the mili- tary coup of the Turkish gov- ernment which took place in 1982. The action of the novel revolves around a visit by three young people to their grand- mother, Fatma, who lives in a crumbling mansion on the shores of the Sea of Marmara, an hour’s drive from Turkey’s capital, Istanbul. They come each year to honor her and to visit their grandfather’s grave.

Fatma, in her 80s, now lives alone in her dilapidated house, save for the companionship and service of Recep, a dwarf, who also happens to be the illegitimate son of her deceased husband, Selahattin. Their uneasy, codependent relationship is based on habit, need and uncomfortable circumstance. It is revealed that Selahattin fathered two chil- dren with a servant woman. The children were at first exiled to a remote village, but eventually brought back into the family fold, by Dogan, the legitimate son, who took pity on them. While Recep works as Fatma’s servant, his brother, Ismail, who sells lottery tickets, has built a house nearby, and has a son, Hasan, whose political connections will eventually draw the family into the nationalists’ struggle to control the future of Turkey.

The three grandchildren, Faruk, Metin and their sister, Nilgun, are still on the cusp of adult- hood, still not fully formed as adults or fully responsible for their lives. Faruk, the eldest, an obese alcoholic, has chosen to be a historian, and he pursues his profession obsessively, but erratically, delving into obscure archives, taking notes, in a vain attempt to capture his elected subject. He has been married, but his wife has left him and he muses often on the pointless- ness of his task.