By Edmond Y. Azadian

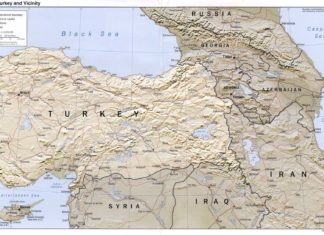

I am back in Cairo, Egypt, in this most turbulent of times. This is a city which I called home for almost a decade when I was invited to serve as the editor of the daily Arev, established in 1915 by its founding editor, Vahan Tekeyan, who is generally celebrated among Armenians worldwide as a poet.

My term as editor coincided with the Gamal Abdel Nasser era, when patriotic fervor was in abundance, balanced with the scarcity of commodities and food staples. At that time, contrary to outside adverse publicity, the government treated the Armenians and minorities with kid gloves, as long as our community observed a cool distance in its relations with Soviet Armenia. Visiting dignitaries, artists, clergy and writers were under vigilant scrutiny, but welcomed anyway.

Armenian churches, schools, cultural centers and newspapers were tolerated and well-protected, sometimes with that official “affection” bordering on a “bear-hug.”

Upper middle class Armenians suffered across the nation as a consequence of the Arab socialist experiment, which some people took erroneously as directed only at minorities.

In the aftermath of World War II, the Egyptian-Armenian community was 45,000-strong, only to be reduced to less than 5,000 today.