Special to the Mirror-Spectator

PLAISTOW, N.H. — What does a New Hampshire high school wrestling coach have in common with one of the most beloved Armenian kings in history? Simple: they both excelled in wrestling.

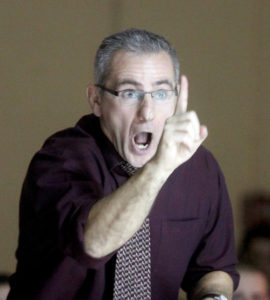

Barry Chooljian is a longtime wrestling coach at Timberlane Regional High School in Plaistow. In his almost three-decade coaching career, he has amassed a trophy pile that rivals Tom Brady’s. In fact, just last season he passed 500 career victories as a coach, a number few have reached. His impressive resume includes 21 Division 1 New Hampshire state championships, 10 New England titles and a National High School Coaching Association’s Wrestling Coach of the Year award.

Tiridates III, before becoming King of Armenia in 287 AD, was an Olympic champion in wrestling at the 265th Olympiad in 281 AD. Tiridates would later go on to make Christianity the state religion in 301 AD.

Wrestling has its roots going back millennia in Armenia. One of the earliest forms of wrestling — known as Kokh — originates in Armenia. This now-defunct sport was often accompanied with Armenian folk music and dancing, while the participants wore traditional Armenian clothing. Kokh left a lasting legacy in the region, influencing the creation of the well-known modern Soviet martial art called Sambo (short for SAMozashchita Bez Oruzhiya), which literally translates as “self-defense without weapons,” as well as solidifying the importance of wrestling in Armenia.