Mirror-Spectator Staff

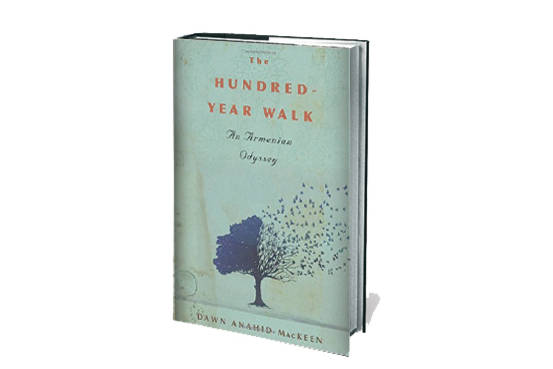

WATERTOWN – With a hundred years now having passed after the start of the Armenian Genocide, the immediacy of the event has most obviously faded away. The generation of survivors of the Genocide is nearly all gone now from the earth, and even their children are elderly. Nonetheless, the story of the Genocide and the effect it has had on people’s lives still seems to resonate powerfully, and it seems the third generation, the grandchildren of survivors – the last generation in direct contact with these eyewitnesses, is now carrying the torch. The number of new books on the Genocide and its consequences which have been published over the past few years attests to this. Dawn Anahid MacKeen’s The Hundred-Year Walk: An Armenian Odyssey (Boston, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016) is one of the most recent ones.

Many grandchildren work to get their grandparents’ personal stories heard by broader circles. Some translate memoirs into English, while others transform the experiences they heard about into literature or other forms of art. MacKeen’s approach adds a different layer to the original story. She did not stop at just visiting the hometown of her ancestor in Turkey, as many do. Instead, she wanted to retrace as much as possible the actual journey of deportation and escape by traveling to Adabazar in western Turkey, and then going to the Syrian deserts through the same routes as her grandfather.

Her well written book maintains a certain level of suspense for both story lines, which are developed in alternating chapters. Her mother always implored her over the years to use her skills as a reporter to get grandfather Stepan Miskjian’s story told, and MacKeen wondered to herself, “Nearly a century later, where was my sense of moral obligation? Doing nothing felt like forgetting, and forgetting genocide seemed almost as heinous as the crime itself, especially in light of Turkey’s denials” (p. 7).

MacKeen, who could not read Armenian, did not let the language barrier interfere. Other relatives translated her grandfather’s diaries and she and even her mother learned details that never had been spoken about. However, there were still certain gaps, and there were no contemporaries left who could fill them in. Instead, MacKeen visited libraries in Europe before beginning her own odyssey to Turkey and Syria. She used contemporary Armenian and European newspaper accounts, as well as other memoirs, survivor testimony, history books and collections of archival documents in various languages.