By Edmond Y. Azadian

By Edmond Y. Azadian

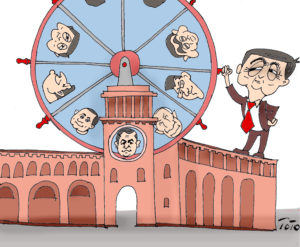

Since its independence 25 years ago, Armenia has had three presidents and 18 prime ministers. Most of the prime ministers have come and gone without much fanfare. However, the resignation of Hovik Abrahamyan and his replacement with Karen Karapetyan have become the subject of much speculation and various interpretations.

Abrahamyan has served the country for the past three and a half years. Before that, he forced himself into the position of speaker of Parliament, pushing aside the more refined and erudite statesman, Tigran Torosyan.

His appointment as prime minister came with promises of important economic improvements. Not only did those promises prove hollow, but the state debt crossed the threshold of $5 billion, as the Economist wrote in a recent article.

When Abrahamyan became prime minister, many in Armenia were appalled, as he lacks the polish that his predecessors have had, and many worried that he would embarrass the country in foreign diplomatic circles.

The business acumen which had helped him hoard his personal wealth did not help the country in any way. Instead, he honed his skills in playing games of intrigue and using electoral fraud for gain, which further tainted Armenia’s image as a corrupt country.